We all knew that Oscar Wilde was a bit of a lad, and those of us who enjoyed Mike Collins’s enthralling talk about the Irish poet and playwright now also know that he was something of a chip off the old block. For while Oscar played a central part in the story, Mike’s presentation – subtitled Genius, Eccentricity and Tragedy – helped us understand how Wilde’s character was to a large extent shaped by his intellectual and upper middle class family.

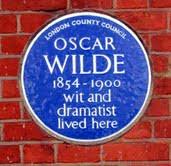

Oscar was born in 1854 to William (later Sir William) Wilde, a prominent Dublin ear and eye surgeon, and his wife Jane Elgee, a noted poet, feminist and socialite. He was home educated to the age of nine, with French and German governesses, and became fluent in both languages. After university in Dublin and Oxford, where Wilde proved himself an outstanding classicist, he moved to London and into fashionable cultural and social circles.

He embraced the rising philosophy of aestheticism, a literary and artistic movement which was devoted to ‘art for art’s sake’ and which rejected the notion that art should have a social or moral purpose. He published a book of poems, and lectured in the United States and Canada on the new English renaissance in art, before returning to London where he worked prolifically as a journalist.

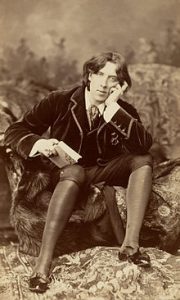

Known for his biting wit, flamboyant dress and glittering conversational skill, Wilde became one of the best known personalities of his day.

He had been introduced in 1881 to Constance Lloyd, daughter of a wealthy QC. She happened to be visiting Dublin in 1884 when Wilde was lecturing at the Gaiety Theatre. He proposed to her, and they were married at the Anglican St James’s Church in Paddington, London.

But Wilde was leading a double life. At the height of his success, Wilde had the Marquess of Queensberry prosecuted for criminal libel after the latter had left a calling card at Wilde’s club, the Albemarle, on which he scribbled: “For Oscar Wilde, posing as Somdomite (sic).” The Marquess was the father of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. The libel trial unearthed evidence that caused Wilde to drop his charges and led to his own arrest and trial for gross indecency with men. After two more trials he was convicted and sentenced to two years’ hard labour from 1895 to 1897.

Upon his release from Reading Gaol, Wilde left immediately for France, never to return to Ireland or Britain. There he wrote his last work, the Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898), and he died destitute in Paris from cerebral meningitis at the age of just 46.

Mike Collins graduated from University College, Galway, in 1973, and his interest in Wilde and his family stems largely from the fact that he grew up in the same town, Castlerea, Co Roscommon, as William Wilde, himself the son of a prominent local medical practitioner.

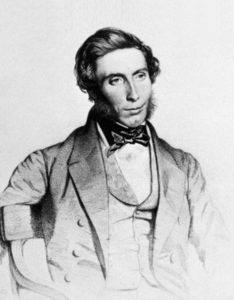

Mike drew comparisons between Oscar and his father. For although Sir William became pre-eminent in his field, becoming wealthy enough to open his own private hospital in Dublin, St Mark’s Opthalmic Hospital, in 1844, and being appointed as Oculist-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria, his later life was also mired in controversy.

His reputation suffered irreparable damage when Mary Travers, a long-term patient of Wilde’s and the daughter of a colleague, claimed that he had seduced her two years earlier. She wrote a pamphlet crudely parodying Sir William and Lady Wilde and portraying him as the rapist of a female patient anaesthetised under chloroform.

Lady Wilde complained to Mary’s father, Robert Travers, which resulted in Mary bringing a libel case against Lady Wilde. Mary Travers won the case but was awarded a mere farthing in damages, while legal costs of £2,000 were awarded against Lady Wilde.

Then, three years later, the Wilde’s daughter Isola died of fever at the age of nine. In 1871, the two illegitimate daughters of Sir William burned to death in an accident, and in 1876 Sir William himself died. The family discovered that he was virtually bankrupt.

Lady Wilde, who wrote under the pseudonym Speranza, was an early advocate for women’s rights and gained a reputation for pro-Irish independence and anti-British writing. She wrote an article for The Nation calling for armed revolution in Ireland, as a result of which the magazine was permanently closed down by the authorities.

Oscar and Constance Wilde had two sons, Cyril (1885) and Vyvyan (1886). After Oscar’s imprisonment, Constance changed her surname to Holland and, although not seeking a divorce, denied parental rights to Oscar.

According to Vyvyan Holland’s accounts in his autobiography, Son of Oscar Wilde, Oscar was a devoted and loving father to his two sons and their childhood was a relatively happy one.

At the start of his presentation Mike had run a few of Oscar Wilde’s witticisms past us, including one of the best known: “What is a cynic? A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” Personally, the one I like the best was reputedly uttered as he lay dying in a dingy hotel room in Paris. “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has to go.”