When Dennis Ashton last came to speak to us, just over five years ago, his subject was dog sled racing in Alaska, where he also witnessed a superb auroral display which probably gave him the inspiration for his latest talk.

Dennis, a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, kept us enthralled for an hour with his slideshow presentation on the story of the space race so far, the day-to-day problems facing the 236 astronauts who have spent time on the International Space Station, and what the future holds in terms of space travel.

Dennis predicts that China will be the next nation to reach the moon, and that in 200 years’ time there could be a city on Mars. Before then, an international mission to land humans on Mars is scheduled for 2040.

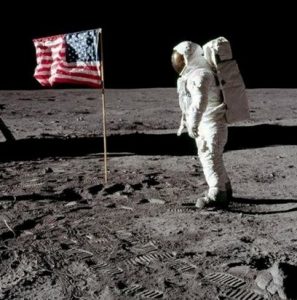

And when, in 200 years from now, people look back on key moments in the space race, he believes the two great iconic images will be the Apollo moon landing and the development and construction of the International Space Station, where man learnt to live in space.

Man first stepped foot on the moon on 21st July 1969, and various events are planned to commemorate the 50th anniversary in two months’ time. A new blockbuster documentary film, entitled Apollo 11, is due to be screened at Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema on 7th June.

Dennis’s talk was chiefly about the International Space Station, a multinational construction project that is the largest single structure humans have ever put into space. It is roughly the size of a football pitch. Its main construction was completed between 1998 and 2011, although the station continually evolves to include new missions and experiments. It has been continuously occupied since November 2000.

The ISS travels at a speed of almost five miles per second, or 17,500 miles per hour, orbiting the earth every 92 minutes while the six astronauts on board either carry out scientific experiments, undertake maintenance work on the giant structure, eat, exercise, relax or sleep, depending on the time of day (which, as a matter of interest, is aligned to Greenwich Mean Time). The construction of the ISS involved no fewer than 40 space shuttle flights between 1998 and 2010.

Whether you are a would-be space traveller or an accountant, the statistics are equally staggering. Between 1985 and 2015, the bill for developing the ISS amounted to $150 billion, and the annual running costs come to $5 billion. The United States have paid by far the largest amount, around $126 billion, with Russia adding $12 billion, Europe and Japan each chipping in $5 billion and Canada $2 billion.

The crew on the ISS work a 15-hour day, from 6am to 9pm, but that includes three meal breaks and two and a half hours’ exercise, which is essential if muscles and bones are not to waste away. There is an hour’s relaxation before the astronauts get eight hours sleep. They do not go to bed as such; in the weightless conditions of the space station, each astronaut has a personal space where their sleeping bag is suspended on a wall, and they simply zip themselves into it.

We saw Britain’s own Major Tim Peake, who spent 185 days in orbit, doing everything from carrying out highly skilled scientific experiments to doing his ablutions, the latter also needing a fair amount of skill. Washing is more like a quick rub down with an oily rag as there is no running water, no shower and no bath. Clothes are worn for a set number of days and then discarded, finishing up in a sealed container along with human waste and then jettisoned in a supply vessel which burns up on re-entry to the earth’s atmosphere. However, 90 per cent of water used, including that which has passed through the six astronauts the previous day, is recycled and re-used, to the tune of around 6,000 litres a year, although there is also a back-up supply of 2,000 litres on board.

All meals are dehydrated and water pumped into the container of dried food as and when needed. Drinks are vacuum packed and sucked through a plastic straw. The only fresh food such as fruit come on board when a shuttle arrives with new crew members. Bread is not allowed because of the danger of crumbs finding their way into delicate equipment, so wraps are the favoured option.

It all seems a pretty miserable existence to me, and probably to anybody else who likes their creature comforts, and yet wealthy individuals are reportedly prepared to pay $20 million each for the privilege of a 10-day holiday on board the space station. Give me Bognor Regis any day.