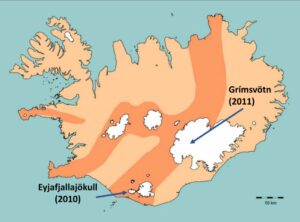

The mention of Icelandic volcanoes takes most people back to the 2010 eruption, when fine ash caused widespread disruption to air flights over northern and western Europe from April to July.

But the eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull in the south of the country were but a drop in the ocean – probably literally for most of the ash – when compared with earlier recorded eruptions and potentially even greater ones to come.

Dr Dave McGarvie, a Scot who has worked in Yorkshire in the past but is currently an honorary research fellow at Lancaster University, specialising in volcanism, kept 45 of our members and guests enthralled during a one-hour illustrated talk on Iceland and its volcanoes.

This was an addition to our current programme of twice-monthly Zoom presentations during lockdown, brought forward because Dave, after being grounded not by volcanic ash but by Covid-19 in 2020, is hoping to get the green light to carry out another six weeks’ research in Iceland during the coming summer.

The 2010 Eyjafjallajökul ash cloud caused so much disruption because it was, as Dave explained, a ‘perfect eruption.’ It was unusual on four counts – it occurred during a prolonged spell of dry weather, a higher proportion than normal of the ash was very fine, the winds at the time carried the ash directly towards the UK and the rest of Europe, and it was unusually long-lived for its size, producing ash for 39 days.

In addition, all aircraft were grounded because of inflexible flight rules.

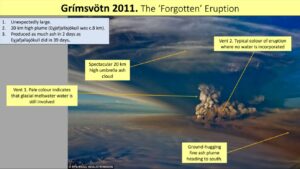

By comparison, the Grímsvötn eruption to the north east of Eyjafjallajökull in 2011 – known as the forgotten eruption – resulted in a 20-kilometre high plume, compared with Eyjafjallajökull’s plume of around eight kilometres, and produced as much ash in two days as Eyjafjallajökull did in 39 days.

In July 2011, a few weeks after the eruption ended, Dave travelled on the first expedition to the eruption site to study it and collect samples before snow covered the evidence.

Our next port of call during Dave’s talk was Askja, a volcano in the central east of the country which last erupted in 1961 but which, he assured us, would definitely erupt again. In 2014 there was a large landslide and a ‘tsunami’ which exceeded 50 metres in height and washed a great deal of pumice from an earlier (1875) eruption into the water-filled caldera (Spanish for boiling pot – GS) formed by that eruption and, at around 257 metres, the deepest freshwater lake in Iceland.

Dave then took us to the especially scenic Eastern Fjords, and on to Hvalsnes, which means ‘Whale Point’ where lookouts used to watch, and which has a reputation as one of the windiest places in Iceland, as he found out in 2003 when the windows on the seaward side of his parked minibus were smashed by flying sand and pebbles driven by a wind of around 140mph.

Öraefajökull, in the south east of the country, is Iceland’s largest and tallest volcano, with a diameter of 25 kilometres at its base and a height of 2,000 metres. Öraefajökull had a huge eruption in 1362 and its last was in 1727-28. But in June 2017, there started what Dave ominously described as a ‘period of unrest.’

If anybody is planning a holiday to Iceland, that might be a good place to avoid. Or at least wear a hard hat.

- All images via Dr Dave McGarvie