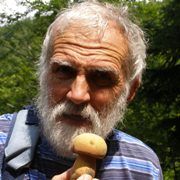

Dr Patrick Harding soon established himself with the audience as a fun guy, but although fungi were certainly on the menu this was a pot pourri of tales about the hidden qualities of all sorts (and Allsorts) of everyday plants.

And they were tales, rather than tedious botanical descriptions. Green fingered I most certainly am not, and the title of Patrick’s talk, A Plant Anthology (Stories about Wild and Garden Plants), hardly filled me with eager anticipation. But it quickly became clear that Patrick was an entertaining and gifted speaker, and he had our undivided attention for every minute of his one-hour presentation.

It was a collection of true stories about plants, to quote the preamble to his book Patrick’s Florilegium which formed the basis of the talk. He looked at plants in medicine, folklore, poetry, history and industry. From lesser celandine and Wordsworth, to the role played by horse chestnuts during two World Wars, the medicinal use of meadow saffron, yew and melilot and the historic use of seaweed in glassmaking.

And, yes, I too had to look up the word ‘florilegium’ – an anthology, from the Latin floris, for flower, and legere, for gather.

Dublin-born Patrick, who turned 70 last week, is a freelance broadcaster, author and adult teacher. He was for 20 years a lecturer at Sheffield University, and organises the science programme for the Institute of Continuing Education at Cambridge University. He has appeared on television and radio programmes such as The Flying Gardener, Castle in the Country, Richard and Judy, BBC Breakfast, Britain’s Best Wildlife, Radio Four’s Up Country and Radio Two’s Chris Evans Show.

He started with the big stuff – trees such as the sycamore and lime (neither of which are native to Britain) and the yew, which for hundreds of years has been synonymous with English churchyards but which, ironically, produced timber for the manufacture of longbows. “What would a church be doing, growing a weapon of war?” he asked rhetorically.

The poet William Wordsworth’s favourite flower was not the daffodil, as widely believed, but the lesser celandine, an example of which is carved on his gravestone at Grasmere. But in Wordsworth’s day the plant was known as the pilewort and, perhaps because the tubers on the stem of the plant below ground looked remarkably like haemorrhoids, was widely used to treat that complaint.

I need not have worried about the overuse of Latin names for the plants Patrick was describing. Arum maculatum is sometimes known as cuckold’s tinsel, but in the south of England is often called lords and ladies while in Yorkshire, where they call a spade a spade, it is apparently better known as dog’s dick.

Many plants contain starch, and in the Middle Ages the use of food for anything but eating was frowned upon so non-edible plants were used for laundry purposes.

The game of conkers was originally played with snails’ shells (at least, I presume it was merely the shells), and it was only when spreading chestnut trees started to be grown in Britain’s parks and country estates that the hard fruit, or seed, of the horse chestnut became the conker as we know it today.

But conkers had homeopathic qualities, too, and chemicals from the conker could also be converted into acetone which was used in the production of the explosive cordite in both World Wars.

The melilot plant, from the Latin mel for honey and also known as yellow sweet clover, contains the anticoagulant toxin dicoumarol which can lead to internal haemorrhaging and death in cattle but is used in the production of warfarin.

Next we came to wild liquorice, well known to Yorkshire folk, which is bad for blood pressure but which contains an anti-inflammatory which was used in the treatment of ulcers. It can also have a purgatory effect, as Spike Milligan found to his cost when working as a van boy for a firm delivering confectionery. “I ate so many Bassett’s Liquorice Allsorts that I had the sh*ts for a week,” he was quoted in his biography.

Meadow saffron, which produces a drug for the treatment of joint pain, can have a similar side effect.

The mandrake plant has a long history of medical use and its root, which is hallucinogenic, was said to improve women’s fertility. The potion was apparently smeared on the shaft of witches’ besoms. Bryony, which is similar in appearance, was also used but was apparently less efficient – a little like some online brands of Viagra, Patrick told us.

The ash produced from burning seaweed is used in glass production, allowing sand to melt at a much lower temperature than the 900 deg C otherwise needed. Seaweed is also used in the production of surgical dressings because it absorbs blood and pus.

Camomile, a very fashionable drink these days, has a calming effect where almost all other beverages contain stimulants. “Twenty million Germans drink camomile in the evening, leading to a night’s restful sleep, which is probably why, by the time you get down to the pool, they have already put their towels on the sunbeds,” Patrick explained with a delightful lack of political correctness.

Oh well, I’m sure most of the other nuggets of information in Patrick’s talk had a sound scientific foundation.