Geoff Gill, Emeritus Professor of International Medicine at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and Liverpool University, and a retired NHS Consultant Physician, gave us an illuminating talk on the privations and diseases experienced by Allied prisoners of war during the building of the Burma railway. He gave an often harrowing account of the suffering experienced by those unfortunate to be part of the Allied garrison – based primarily in Singapore – following surrender to the Japanese in 1942, and the truly ingenious efforts to provide respite from appalling symptoms of the various diseases that were endemic in the camps set up to construct the Burma Railway.

A total of approximately 140,000 allied troops were captured, with up to 100,000 housed in the notorious Changi camp in the north east of Singapore Island, enduring poor sanitation and a very poor and limited diet, mainly of rice, leading to dysentery, beriberi, cholera and vitamin deficiencies.

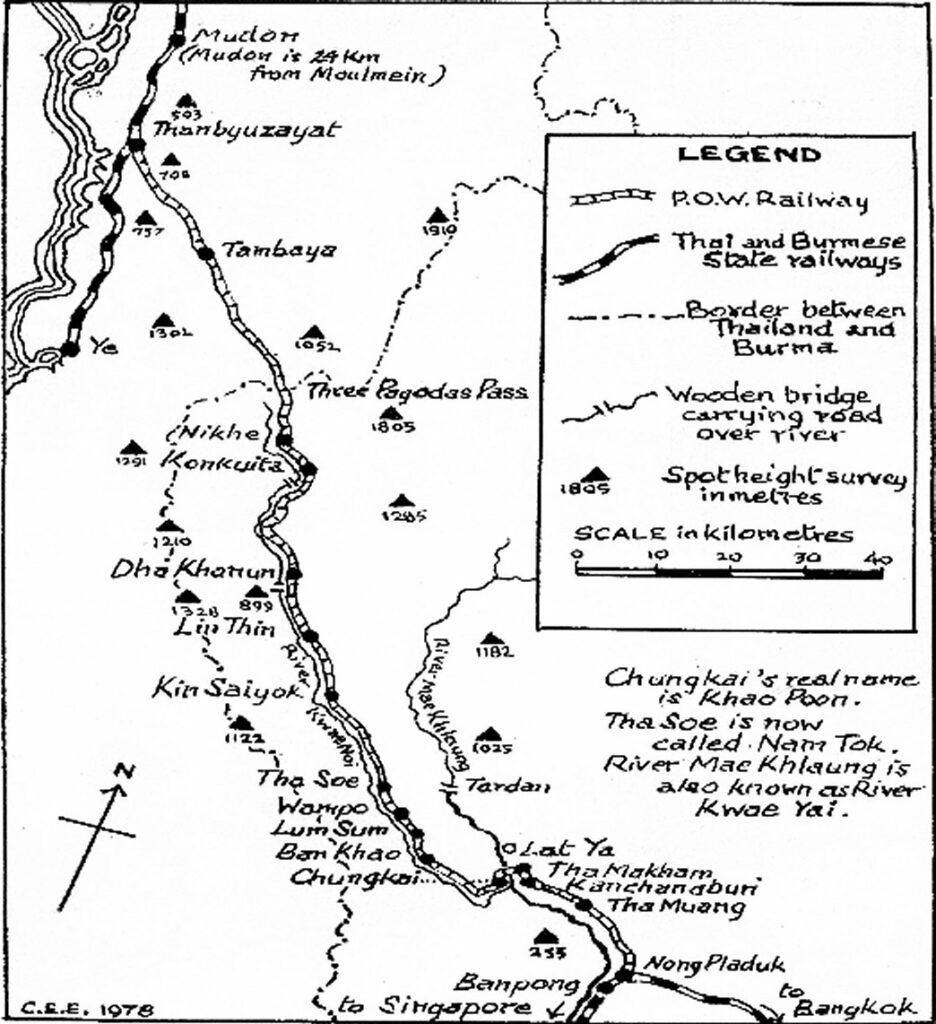

Many of the POWs were eventually moved to up-country camps with even poorer facilities to commence the construction of the railway, some 415 kilometres in length across difficult mountainous jungle terrain. A chilling statistic highlighted by Prof Gill was that the cost of completion was a life lost for every railway sleeper laid.

The workforce was made up of 60,000 POWs and 150,000 ‘volunteers’ with additional specialist advisors from within the Japanese forces. Although the conditions were difficult and the treatment often brutal, the railway was completed by October 1943 despite the British Government having abandoned a similar project previously as unachievable.

The health of both the POWs and volunteers suffered greatly, with significant loss of life with up to 50 per cent mortality rates in the outlying camps affecting not only the prisoners but also the volunteers and to a lesser extent, but still in excess of normal rates, the Japanese.

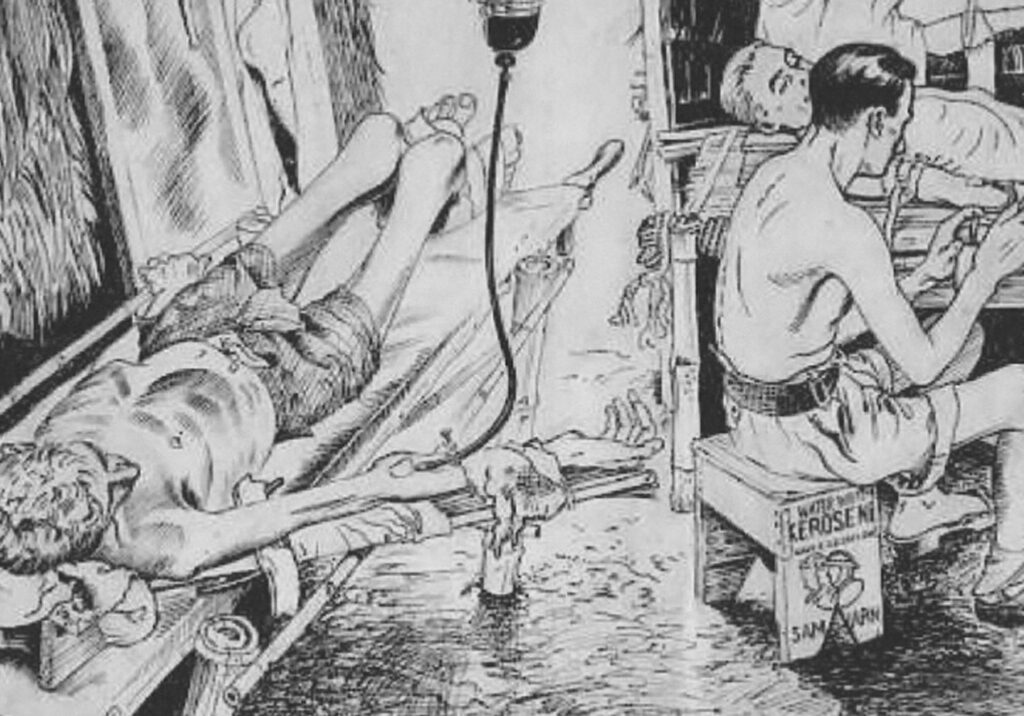

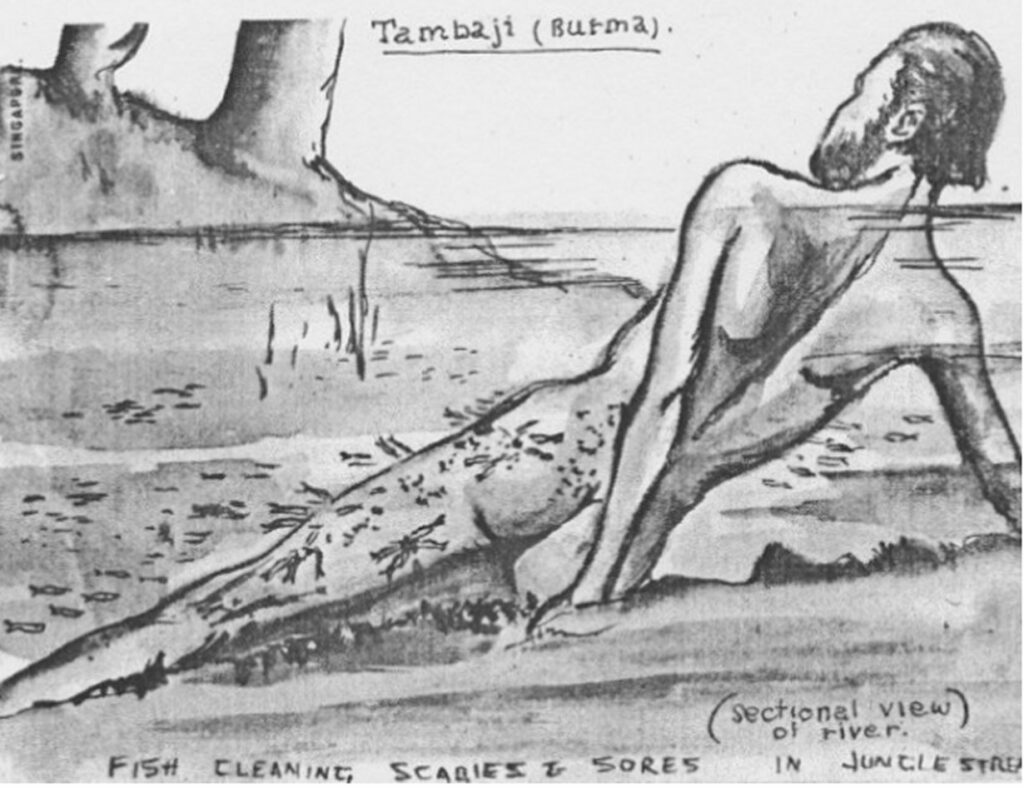

Hospital camps housing up to 3,000 patients at a time were set up and, with great ingenuity, treatments for the severe effects of diseases and tropical ulcers were devised utilising the limited medical supplies available and local products such as bamboo which could be fashioned into syringe needles, old bottles used to set up intravenous drips and even dental equipment and bathing in rivers to allow fish to clean up ulcerous flesh.

At the end of the war survivors returned by sea to Liverpool and Southampton with long term care being undertaken, most particularly at The School of Tropical Medicine in Liverpool which had specialist staff who provided healthcare from 1945 to 1999. Despite the setting up of resettlement units at the end of hostilities, many troops – whether POWs or returning serving soldiers – did not attend, and many suffered not only physical long term issues as a result of their internment but also psychological problems over many years, these now being defined as PTSD though this was not recognised until the 1980s. The aftermath of the various diseases included liver cirrhosis, liver cancers, Hepatitis B, parasitic worms (some of which persisted for over 60 years), psychiatric problems and nerve damage following prolonged vitamin deficiency.

The Liverpool Hospital took over 4,000 patients and undertook long term care and research which continues to inform not only the military establishment but the wider medical world of the effects, some long lasting, of both physical and mental trauma.

The talk was followed by a lively question and answer session, with thanks being given to Prof Gill for his detailed and well presented talk.