Think of Barnes Wallis and thoughts go to Dam busting bouncing bombs accompanied by Eric Coates’ splendid 1955 film signature tune. Our speaker this week, Peter Rix, opened his presentation by reminding us that his subject’s achievements were much wider that those associated with the exploits of 617 Squadron at Mohne and Eder. Wallis’s portfolio of leading or contributing to major high-tech projects was to span over sixty years and was to include ships, submarines, airships, aircraft (piston engine to hypersonic), telescopes, torpedoes, heavy bombs and last, but not least, school hot water systems!

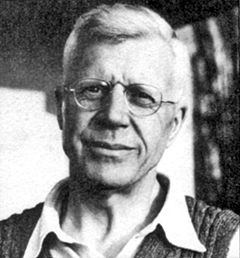

Barnes Wallis was born son of a doctor on 26th September 1887 in Ripley, Derbyshire. He gained a scholarship to Christ’s Hospital School, Sussex. At 16 faced with the choice of Classics or more Classics, he opted instead for a marine engineering apprenticeship at Samuel White’s yard in Cowes Isle of White. While there he took a London University Degree in Engineering in six months! Wallis left White’s in 1913 to work for Vickers shipyard at Barrow in Furness. Later, he took Maths teaching post in Switzerland when the opportunity occurred for him to return to Vickers to work on airship design at Howden, including the R (for rigid) 100. This included the first use of light alloy geodetic construction (integrating both body structure and shape) in the largest airship ever built -at over 700ft long with eleven miles of tubing. Despite better than expected performance and a successful return flight to Canada, the R100 was broken up in 1930 following the crashes of its rival “sister ship” R101 and the German ‘Zepperlin’ Hindenburg.

Following the abandonment of airships, Wallis was transferred to the Vicars aircraft factory at Brooklands, Surrey. The aircraft designs of the Wellesley, Warwick, Windsor and Wellington all employed Wallis’s robust geodetic design in the fuselage and wing structures. When World War Two began in 1939, Wallis was promoted to Assistant Chief Designer. He was about to make his mark on history.

In February 1943, Wallis, concerned to find targets which could not be moved or easily replaced, revealed his idea for air attacks on Dams in Germany. ”If the destruction or paralysis of power supplies can be accomplished they offer a means of rendering the enemy incapable of continuing to prosecute the war”. One ton of steel requires 100 tons of water. From ricocheting marbles in a bathtub he developed a sphere-shaped rotating bomb (Codename ‘Upkeep’) that would bounce over water clear of protective netting, roll down the dam’s wall and its hydrostatic fuse trigger explosion at its base. The weight of water would do the rest.

Operation Chastise was carried out on the night of 16-17 May 1943 by the specially created 617 Squadron led by Guy Gibson. What happened next is well known. Perhaps the most significant result was the hugely positive effect on Allied morale but Wallis much regretted the loss of (especially aircrew) life.

When the decision was taken to concentrate on area bombing, Wallis began looking at the design of aircraft that could drop heavy bombs. The adapted Avro Lancaster was capable over dropping two bombs (which he also invented). The ‘Tallboy’ designed in 1944 (there is an example at Kelham Island) and used to sink the German Battleship ‘Tirpitz’ and the ‘Grand Slam’ earthquake bomb the following year. Both were used against major infrastructures such as railway tunnels and viaducts and heavily fortified targets or production centres for the ‘V’ rockets and submarine pens.

After the war, Wallis led aeronautical research and development at the British Aircraft Corporation. He led his team on many futuristic projects including supersonic flight and ‘swing wing’ aircraft. His work on aerodynamics (aided by his ‘Stratosphere Chamber’ now restored at Brooklands) was to influence such developments as the TSR-2 and Concorde. But much of his later work was frustrated by lack of supportive funding and the increasing loss of expertise and markets to the Americans. It was to be same story in other areas such as rocket-propelled torpedoes, commercial submarines and remote controlled aircraft. He was consultant to the Parkes Radio telescope project in Australia.

Barnes married his wife, Molly Bloxham in 1924. At seventeen years his junior, her father had strong reservations but he allowed them to continue a courtship through correspondence which seemed more about physics and differential calculus than romance! There were four children and the couple fostered two more. They settled and lived at Effingham for the remainder of their lives.

Wallis became a member of the Royal Society in 1945 and knighted in 1968. He was awarded the sum of £10,000 for his war work from the Royal Commission on Awards to inventors. A kindly and God fearing man, his grief at the loss of so many airmen in the dams raid was such that Wallis donated the entire sum to Christ’s Hospital School in 1951 to allow them to set up the RAF Foundations’ Trust, allowing children of RAF personnel killed or injured to attend the school.