Early life

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (neé Pierrepont) is recognised as one of the great female intellectuals of the 18th century.

She was the daughter of the Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull, born in 1689. Between 1692 and 1700 she went to her grandmother at West Dean near Salisbury, then to Thoresby Hall near Ollerton. Here she was educated (badly) by a governess, but intellectually motivated, she taught herself Latin and immersed herself in books.

In London she met Edward Wortley Montagu, grandson of the Earl of Sandwich. Through his sister Anne Wortley, Edward made it known he was keen on Lady Mary and they continued to correspond and meet secretly. However arranged marriages were common amongst the aristocracy and Clotworthy Skeffington, an Irish Peer, was her father’s alternative idea of a suitably wealthy aristocratic suitor. Edward’s counter proposal was flatly rejected by Lord Dorchester so they eloped and married in 1712. Their son Edward junior was born in 1713.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu with her son Edward

The following year Edward (senior) accepted accepted the post of Junior Commissioner of the Treasury. Mary rose to the highest levels of the social ladder in London and was introduced to the royal court. A bit of a scandal monger, she wrote anonymous poems for The Spectator between 1714-16, describing members of royalty as “blockheads”.

In 1716 Edward was posted to Constantinople as British ambassador to negotiate an end to the Austro-Turkish War. They travelled overland via Vienna, accompanied by 200 Turkish troops, physician and servants. A daughter was born in 1718. She wrote “Letters from Turkey” and is credited as the first female travel writer.

Lady Mary visited zenanas in the Ottoman Empire to learn about the customs of segregated Muslim and Hindu women. She wrote about a visit to a Turkish bath, her gender and status providing access to female spaces that were no-go areas for men. The Ottoman women were horrified by her stays (of corsetry), believing her to be “so locked up in that machine that it was not in my own power to open it, which contrivance they attributed to my husband”. Her writing was somewhat erotic.

A painting, inspired by Mary Wortley Montagu’s detailed descriptions of nude oriental beauties, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

She looked far more comfortable there out of corsetry.

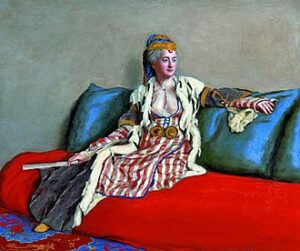

Lady Montagu in Turkish Dress by Jean-Étienne Liotard c.1756

Smallpox

Smallpox was first recorded in China in third century and by the tenth century nasal inoculation of pustular material to achieve immunity was practised.

Smallpox inoculation in China

Pox-swaddling in infected clothes had been used for centuries in parts of Wales to gain immunity. The English were unaware.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu introduced variolation to England, based on her Turkish experience where smallpox was rife. She had survived the disease herself at the age of 26 but her face was disfigured. Her brother had died from it two years earlier in 1713. She was therefore alert to the its implications and in 1717 she wrote about the effective Turkish practise of variolation (inoculation) for smallpox in “Letter to a Friend”. Pustules from an infected person were scratched into the skin of an uninfected person. Acquired immunity resulted in just mild disease and no (documented) mortality with minimal scarring.

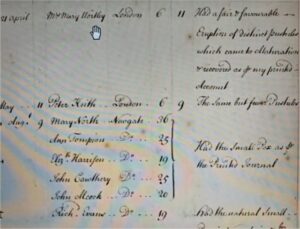

She persuaded Charles Maitland, embassy surgeon, to inoculate her 5 year old son Edward. Back in England in 1721 her daughter Mary (many years later buried in Wortley church) was inoculated by Maitland, arousing the interest of Caroline of Ansbach, Princess of Wales. Maitland was reluctant to do it in the public glare of London, fearing the potential scandal of unintended death with an untried remedy! He would only agree on condition that representatives of the Royal College of Physicians were present as witnesses.

Controversy raged. More “clinical trials” were needed. In 1721 the King agreed to pardon six condemned Newgate prisoners if they agreed to volunteer for variolation. All survived and were pardoned. Maitland kept impeccable records.

Six Newgate prisoners pardoned

In 1722, six orphans also survived variolation under scrutiny and royal approval was finally granted. The Princess of Wales had already lost one daughter from smallpox and wished to be inoculated, together with her son and two other daughters. Even then, the “antivaxxers” were hard at work.

Variolation was not completely safe. Deaths subsequently happened. In the 1760s there were multiple anecdotal reports of protection against smallpox by prior cowpox infection, a closely related virus but distinct from smallpox and never producing other than mild symptoms in humans. Cowpox was particularly common in milkmaids. In 1774, farmer Benjamin Jesty inoculated his family with pustular material from infected cows and the children remained healthy in a subsequent smallpox epidemic.

Edward Jenner vaccinating

In 1796 Edward Jenner ( inoculated James Phipps with cowpox from milkmaid Sarah Nelms. He was the first to apply science when he later variolated Phipps, this time with actual smallpox, and he was immune. Jenner’s results were met with initial scepticism but by 1800 vaccination was increasingly accepted. The term “vaccination” was a Latin nod to its origin (vacca=cow).

The modern smallpox vaccine contains vaccinia virus, closely related but genetically distinct from cowpox. Smallpox was declared eradicated by WHO in 1980 shortly after an accidental, but fatal, laboratory escape in Birmingham in 1978 (COVID analogy here?). The blogger considers himself lucky to remain alive after his student days doing a virology course at St Mary’s where the only live English stocks of smallpox virus were kept only feet away in a freezer at the time before their final journey via Porton Down to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta Georgia.

The blogger also recalls the original preserved hide of the donor cow Blossom in the library when he worked at Jenner’s alma mater, St George’s Hospital at Hyde Park Corner. When the hospital was transferred to Tooting in 1977 it went to its current home at the Jenner Museum at Berkeley, Gloucestershire.

Blossom

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s later years

Lady Mary continued to write satirical articles and published her newspaper “Nonsense of Common-Sense” but her outspoken behaviour was increasingly embarrassing to her husband, which led to separation and divorce. When she was 47 years old she met 24 year old Algarotti which caused a bit of a scandal. She left for Venice but the fact that Algarotti was bisexual didn’t help. Having then settled in Avignon in 1742, the English and French went to war in 1744 and she returned to Italy.

Her son Edward was a tearaway, drunkard, burglar and bigamist with an illegitimate child, before absolving himself with a distinguished career in the army. They didn’t get on.

Lady Mary joined Count Palazzi in Gottolengo to lead a quiet rural life before returning to England, by which time she had written her travel diaries. Lady Mary’s daughter refused publication, but shortly after her death from breast cancer in 1762, they were published in the Netherlands from copies of the originals which had been quietly stolen and returned without her knowledge.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s extensive body of work is freely available in print but has been poorly recognised until now, but perhaps this is about to change https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0001v84