Professor Ian Rotherham, of Sheffield Hallam University’s Department of the Natural and Built Environment, gave us an entertaining and informative talk on the history and development of Sheffield’s industries not restricted to cutlery and steel but also incorporating lost historic enterprises such as lead smelting, charcoal manufacture, clog making and glass manufacture.

Ian was born in Sheffield, and after his first university degree returned to the city and university to study for his PhD. He has remained here ever since. Ian is a prolific author of not only more than 400 academic papers, but also many books and newspaper articles, and presents regularly on Radio Sheffield.

Ian started his talk by taking us back to the mesolithic period from when there is local evidence of hunter gatherers who fashioned early tools in and around Deepcar. Later, as time passed, industry developed with Chaucer mentioning tool manufacture in the Sheffield area in the period between 1200 and1300. Sheffield however remained a small community of hamlets until the start of the Industrial Revolution in the early 1800s, when smelting of metals, particularly lead, commenced, utilising charcoal from coppiced woodland including Ecclesall Woods where there is a memorial dating back to 1786 to George Yardley who was found burnt to death after, it was suggested, a night in the nearby Rising Sun.

During this time Ecclesall Woods were almost totally denuded of trees, the woods we see today having been replanted by Earl Fitzwilliam. Woodlands also provided materials for the production of besoms (brooms), used for not only sweeping up but also in the steel industry for many years to remove slag from forged and molten steel until the introduction of chemical products sourced from the USA in the 1960s.

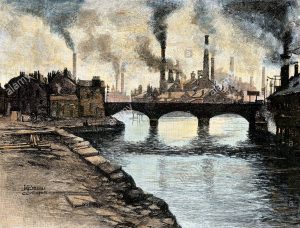

As industry developed, the population of Sheffield exploded from a modest 30,000 in the 1800s to more than 300,000 by 1875 or thereabouts, the living accommodation for the majority being very basic, lacking amenities in cramped and dirty surroundings with polluted rivers and smog. Added to that, poor diet and harsh working conditions led to illness, disease and much restricted life spans. Workers often had a life expectancy of 20 years in 1843. Employment commonly started at the age of eight, with apprenticeships starting at 13 and working hours often being 70 hours a week with 12-hour shifts.

The city did not enjoy a good reputation in this time, being described by George III as “a damned bad place,” with George Orwell stating that in his opinion “even Wigan is beautiful compared to Sheffield“ and “the ugliest town in the Old World.” Things did not improve much until the latter part of the 20th century notwithstanding the improvements in water supply and drainage. Despite the first reservoir in the city being built at Barkers Pool in 1631, the country was swept by cholera in the mid 1800s.

Ian described the expansion of industry being boosted by the presence of a good water supply for power, before the steam engine, coal and minerals, the city attracting many innovative engineers and businessmen such as George Wilson and James Brown who together with many others changed the face of the city across this period and throughout the 20th century. Ian also made the point that the population required support from surrounding farms and villages for local food production, there being no railways or efficient transport infrastructure.

Ian concluded his talk referring to the more modern era including the Simplex motor car, the AMRC and the work he and his colleagues are doing to continue research into the city’s industrial and agricultural past. There was little time for questions, given the extent of his talk which was enjoyed by all.