As a Senior Coroner, our speaker this week, Christopher Dorries, was well qualified to examine the trial of Dr Crippen. In a fascinating presentation we were invited, like a jury, to consider the evidence for a case that for over one hundred years had become more legend than fact.

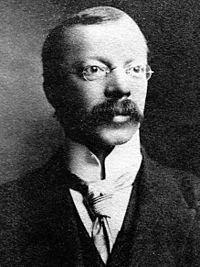

Henry Harvey Crippen was born in Michigan in 1862. Doctor Crippen was an American Homeopath, ear and eye specialist and dispenser of medicine. He was hanged in 1910 in Pentonville prison for the murder of his second wife, Cora, and was the first suspect to be captured and convicted with the aid of wireless telegraphy and forensic techniques. Nearly one hundred years later DNA evidence was to question the identification of the body, which was found to be male.

Henry Harvey Crippen was born in Michigan in 1862. Doctor Crippen was an American Homeopath, ear and eye specialist and dispenser of medicine. He was hanged in 1910 in Pentonville prison for the murder of his second wife, Cora, and was the first suspect to be captured and convicted with the aid of wireless telegraphy and forensic techniques. Nearly one hundred years later DNA evidence was to question the identification of the body, which was found to be male.

Crippen was an insignificant little man, slight in stature and mild in manner, who perhaps surprisingly owned a fire arm, then legal in GB as in USA. In 1887 he married Charlotte Bell, who died in pregnancy in 1892 aged only 33 apparently from a stroke. Within eight months he had married Cora Turner (alias Kunigarde Mackamotski), a ‘would be’ singer who openly had affairs. They lived variously in St Louis and New York, where Cora had surgery to remove her womb and overies, the scar from that operation later being central to the identification of her body.

In 1895 Crippen’s work for Munyon’s, a homeopathic pharmaceutical company sent him to Philadelphia but Cora remained in New York to train in Opera. 1897 saw Crippen transferred to a post in London where he was not qualified to practice as a Doctor. Cora soon joined him but her talents and earnings did not match her determination to spare the pennies while scattering the pounds on costumes and finery. During a brief visit home to America Cora struck up a relationship with Bruce Millar, a music hall actor, sending her marriage to Crippen on a downward spiral. In 1905 the Crippens moved to a new address in Camden where they slept in separate bedrooms. Lodgers were taken to augment Crippen’s meagre income. To make matters worse, Crippen was sacked by Munyon’s for spending too much time on managing Cora’s unfruitful stage career but he found work as Superintendent of a deaf institution. It was here that he met Ethel Le Neve, a young typist who enjoyed bad health but endured bad teeth. Crippen was to take her as his mistress in 1908. Meanwhile, perhaps to compensate for her failures on stage, Cora became Secretary to the Music Hall Guild.

By December 1909 Cora had become tired of with her loveless marriage and resolved to leave Crippen. She had intended to take their savings of £600 but the bank collapsed before she could withdraw. On 19th January 1910 Crippen obtained a large quantity of

the poison, Hyoscin Hydrobromide (found in sea sickness tablets). Crippen later claimed in Court that this was for use in homeopathic prescriptions but he was unable to name a single patient. Less than two weeks later on 31st January, Cora was seen alive for the last time by guests at a dinner party held at their home. Crippen was to claim that Cora had disappeared the following day while he was at work, suggesting that his fundless wife had returned to America. With indecent speed his lover Ethel moved in and she was soon to be noticed wearing several of Cora’s outfits, jewellery and furs. Cora’s sudden disappearance and the couples’s behaviour began to raise suspicions among her artistic friends who started to check the ever changing story which cumulated in her apparent death in USA from pneumonia. One, a Mr Nash, even visited America to confirm that she had not contacted her two sisters living in New York. Having made a fruitless search Nash contacted Scotland Yard on his return.

Chief Inspector Dew (with experience from ‘Jack the Ripper’) was given the enquiry. A superficial search of Crippen’s house was made with nothing found and a statement written over a steak lunch with the suspect. But it was enough to make Crippen panic and he left for Antwerp with Ethel disguised as a boy. Within a couple of days Dew returned to check a few details but found the house empty. Once the alarm raised, descriptions were circulated, ports alerted the house was now thoroughly searched. This time a dismembered body was found under the cellar floor, buried in lime.

A few days later (20th July) the fleeing couple embarked on the SS Montrose, bound for Canada. The Captain, Henry Kendall, observing this odd couple on deck, became suspicious. Using the new wireless telegraphy Kendall contacted London on 22nd July while still in range off the Lizard: “Have strong suspicion that Crippen, London cellar murderer and accomplice are among salon passengers….”

Drew now raced to Liverpool and boarded a faster ship, the SS Laurentic, which was to overtake the SS Montrose en route to Montreal where the couple were arrested on 31st July. Dew had come aboard disguised as a pilot. The trio were to return to London on 19th August.

And so to the trial. The massive press coverage on both sides of the Atlantic would ensure that Crippen could not expect a fair hearing. There was little left of the body but the prosecution claimed that Cora had been identified by a piece of skin with an abdominal scar consistent with her hysterectomy and the high level of Hyoscin found in the body.

This had been buried in a pair of Jones Brothers Ltd pyjamas matching a pair of the same make found in a bedroom. With the evidence stacked up against Crippen the Jury took just 27 minutes to convict him. (Ethel was subsequently found not guilty of being an accessory). Crippen was sentenced to death by no less than the Lord Chief Justice.

Henry Crippen was hanged on 23rd November 1910 only one mile from the scene. Two weeks before he died he wrote “I am innocent and some day evidence will be found to prove it”

And the story did not end there. As recently as October 2007 microscopic slides used by the well known pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury, were analyised. The DNA did not match Cora’s living family and in any event was the wrong sex. If the body was not Cora’s, whose was it? The victim of a botched abortion? The circumstantial evidence at the time strongly pointed to a guilty verdict. But if the trial took place today could we say that such a verdict would be given beyond all reasonable doubt?