David Radstone was a Consultant Radiotherapist and Oncologist at Weston Park Hospital, Sheffield, for 20 years before moving to the Peninsula School of Medicine and finally retiring to Exeter. He gave a superb and beautifully illustrated talk in front of many of his ex-colleagues and even a patient or two.

Egyptian papyrus research shows that cancer treatment began some 5,000 years ago. Hippocrates coined the word ‘cancer’ (the crab). Celsus (25BCE-50AD) categorised breast cancer, differentiating skin ulceration or not and distant spread, an important principle determining survival. There was remarkably little advance in the understanding and treatment of cancer until the late 18th century.

Percival Pott (1775) described occupation-related scrotal cancer in chimney sweeps. The Institution for Investigating the Nature and Cure of Cancer was established in 1801 by relatives and colleagues of John Hunter, whose original huge specimen collection of all things surgical was blitzed and largely destroyed in WWII when the Royal College of Surgeons in London was bombed.

Radiotherapy (RT) began in 1895 after Röntgen’s momentous discovery of X-Rays. The first patient with breast cancer was treated in the same year in Chicago. Röntgen was awarded a Nobel prize for Physics in 1901. Freund (1896) was the first to explore how RT worked.

Public fascination in radiation included X-Rays of the hands of the future King George and Queen Mary. Even photographers got in on the act, offering X-Ray treatment for cancer – very dangerous! This sort of thing went on for half a century more – remember having your feet X-rayed at Clark Shoes? Some of us were also around listening to the wireless when Queen Mary died (nothing to do with RT though). All so relatively recent, and before RT was finally on a safe footing for those giving and receiving it. The first cancer disappearance after RT was in 1896 in Lyon. In hindsight it was probably a lymphoma, now known to be extremely sensitive to X-Rays. It surprised everyone – but the patient died.

Then Pierre and Marie Curie discovered radium in 1898, and were awarded Nobel Prizes. By 1902 Sheffield Royal Infirmary and the Royal Hospital had acquired X-ray machines to treat superficial skin cancer and even non-cancerous conditions such as ringworm or acne, not appreciating at the time that there was a real risk of radiation-induced skin cancer later on in life.

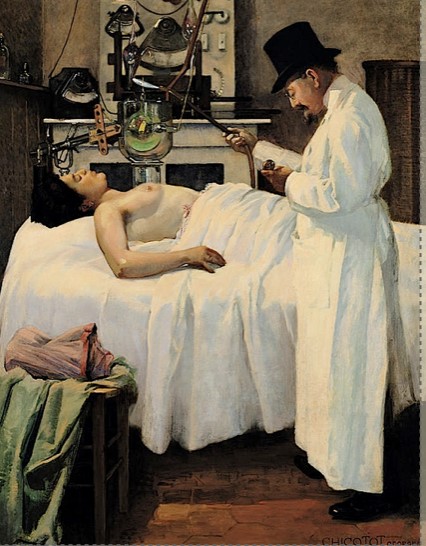

Dose and delivery understanding of X-Ray treatment was pioneered by Belot’s textbook Radiotherapie (1904), then by Nutt in Sheffield and Finzi at St Bartholemew’s Hospital. Georges Chicotot’s self-portrait of 1906 shows him using a watch to time and calibrate the RT dose without radiation protection, just dressed in his top hat, clothing and gown.

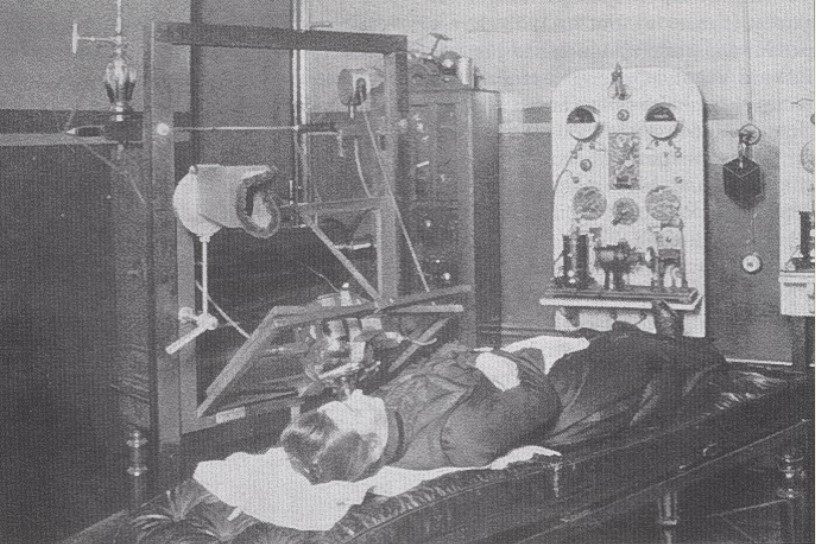

To cope with body contours an X-ray tube on a rail track developed in Sheffield in 1910 delivered RT in multiple directions, more accurately targeting the cancer. This reduced the risk of damaging adjacent normal structures. The Lord Mayor’s Appeal in 1914 brought radium in 1921 to Sheffield from Katanga, via Brussels, Paris and London, unwittingly unprotected and delivered en route in glass bottles. Radioactive radium was hanging around Holborn station for five days at a time, before its onward journey to Sheffield, where treatment began.

Radiography training (radiographers worked and managed the machines) started in 1923 in Sheffield, evolving into a large international centre now based at Hallam University.

The National Radium Trust distributed funds to various centres in the UK, including Sheffield. David Radstone’s mentor was Frank Ellis, educated at King Edward’s School, with JG Graves and Rupert Hallam, and he became Medical Director of the Sheffield Radium Centre in 1930. Graves donated funds to buy two deep X-Ray units. Radium was still being transported around the region without radioprotection in those days. Some radium was lost at the Royal Hospital in 1934 and never found! A major contribution by Frank Ellis was the invention of wedges to modify radium beams. He also developed a clever slide rule to calculate the tolerance dose of RT. Ellis insisted that all potential cancerous nodules were sampled, in case the tumour disappeared after RT “because the surgeons might never have believed it”.

In 1936 modern megavoltage began. The older machines were still unprotected, with incidental radiation to doctors and nurses a future significant problem.

Fingerprints were lost. There was a long-term cancer risk to them. Lead apron protection is now the order of the day. In WWII, RT equipment was moved to Blackbrook Road and patients were treated at Lodge Moor. Radium was transported to the Castleton Caves. Cadavers from the medical school dissecting room went as well – a spooky partnership.

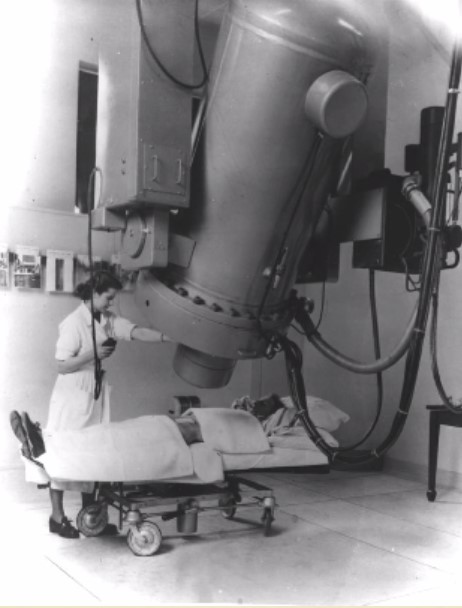

After the war, Frank Ellis persuaded Graves to pay for the new Weston Park Cancer Hospital. This was the emergence of the modern specialty. Blomfield replaced Frank Ellis, who then went to Oxford. New equipment included ‘Big Bertha,’ a van der Graf Generator, produced in Sheffield following the reduction of armament manufacture after WWII. A new hydraulic cobalt unit had much greater freedom of movement, giving more accurate delivery of RT. The source of radioactive cobalt was driven pneumatically into the head of the machine at the point of delivery. Sometimes it got stuck. Abrasion of the tubing was a potential problem with radiation leak in cobalt dust. The brains in Weston Park were actually the physicists who ran the equipment and made it safe.

The Weston Park building began in 1963 but its opening was significantly delayed until 1970. The builders went bankrupt and the new builders couldn’t access the plans.

In recent years, the appointment of some Probus members to consultant posts in Sheffield witnessed huge advances in chemoradiotherapy over their own careers.

Mustine was the first chemotherapy drug. It had started with in WW1 as mustard gas. US soldiers became neutropenic (loss of white blood cells) after exposure. Because the lymphocytes disappeared, it followed that it was logical to treat lymphoma with mustine, the first tumour type to be successfully treated. Some testicular and ovarian cancers were successfully treated with Cis-Platinum There was an explosion of new drugs between 2001-13, resulting in a split of RT from medical oncology, as both were by now very complex and distinct specialties, resulting in over 40 oncology consultants currently appointed at Weston Park.

In conclusion, it is simply staggering that many of our Probus members have been witness to more than 50 per cent of developments in cancer management in their lifetime.