This was a very informative historical talk on tree development within the urban environment. Felicity Stout is the Woodland Manager and Tree Conservation Officer at the Peak District National Park and the University of Cumbria Peak District National Park Authority.

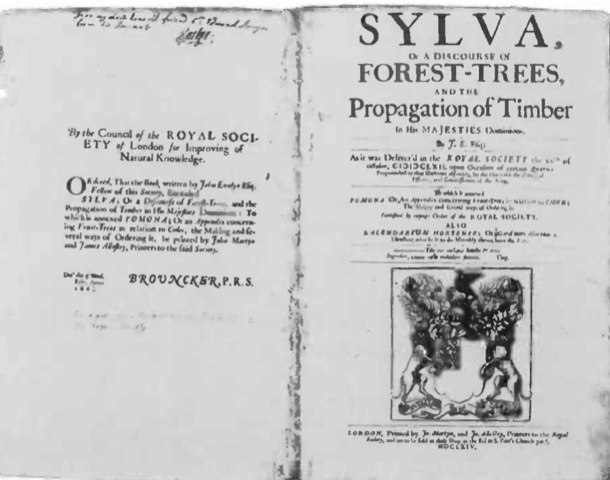

The economic, health and aesthetic advantages of tree planting was recognised here as early as the 16th century but it took until the 18th and 19th centuries before the health benefits of planting trees in industrial areas were fully realised. In ancient Greece and Rome, villas were enclosed in tree-lined avenues. In the Italian renaissance and baroque periods, extravagant gardens and avenues were very much associated with political, aristocratic and regal power. In Shakespearian London, John Stow published his 1598 “Survay of London“, London’s first detailed A-Z street map (Fig 1). For example, “Hogge Lane… had on both sides fayre hedgerows of Ealme trees … easie styles … into pleasant fieldes … to walke, shoote and otherwise recreate…”. John Evelyn’s 1664 seminal work, “Sylva, or a discourse of Forest-trees” (Fig 2), is a renowned text in the history of English forestry and arboriculture. He quoted the Dutch, who appreciated the importance of trees for the benefit of the general public “even in their very roads, and common Highwayes, are better preserved and entertain’d … than…gardens of pleasure belonging to the Nobles and Gentry of other countries” (Fig 3).

After our own Civil War, huge numbers of trees were planted to celebrate the return of the monarchy. James I, in the Age of the Enlightenment, was very keen to support greening of London. Swamp-ridden Moorfields was transformed into tree-lined walks specifically for recreation and for enjoyment. Samual Hartlib, representing the Millenarianism movement, was appointed by Parliament to encourage innovation in the arts and sciences (and presumably facilitate funding).

In order to engage with the “Kingdom of God through radical social improvement”. Arboriculture was included on the back of “Adam’s role in the Garden of Eden.” Each community in England nominated at least one person for highway maintenance. “Chestnut, oake, beech, fruit and elme” were planted for food and fuel, helping the poor. Fruit trees, especially for cider, were conducive to health and long life, purifying the ambient air for health and well-being. Cypress was claimed to help lung problems, largely created by ‘smoak from coal burning.’ Industries burning coal were encouraged to move away from the densely populated city (easier said than done).

Conclusion:

Nationwide, tree planting has provided food, fuel, health, public amenity and employment over the past 400 years.

Some discussion points:

Most of today’s Sheffield’s trees were planted in the 19th century, mainly for aesthetic reasons rather than health. Many are lime trees, which do very well in today’s pollution.

Ash dieback is topical. There are roughly 8 million ash trees in the White Peak, where they lie in damp, less well circulating air currents in deep limestone gorges, ideal conditions for the offending fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus to thrive. The city of Sheffield has better air circulation and ash die-back here is less of a problem.

In 2016, trees were at the mercy of the Sheffield City Council and Amey. Angry scenes erupted when contractors arrived at 5am to fell a number of healthy trees in Rustlings Road, as part of a street improvement scheme, suddenly interrupting this blogger’s sleep across the park. The good news was that the three people arrested for obstruction were released without charge. Felicity explained that better collaboration with tree specialists in the city would have avoided the problem. There’s now multidisciplinary team consultation prior to any future tree felling.