I suppose it all depends who you believe – Pam Ayres or Trevor Wragg.

To quote my favourite female poet’s odd ode: “I am a dry stone waller, all day I dry stone wall. Of all appalling callings, dry stone walling’s worst of all.”

I can’t for a minute imagine Trevor Wragg voicing those sentiments. Trevor lives and breathes dry stone walling, and has been a professional at the job for many years. He was the British champion in 1996, and holds the Dry Stone Walling Association’s Master Craftsman Certificate.

Trevor, who is just coming up his 70th birthday and lives at Hartington, in the Peak District, is a qualified instructor and examiner with the DSWA, as well as serving on that body’s Skills Committee and being an assessor with the National Proficiency Testing Council and the Dales Agricultural and Rural Training Ltd (DART).

He has led assessment days for officers from the Department of Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Peak District National Park Authority, advising them on both good and bad workmanship for grant aided work.

So he clearly knows his stuff, and was just the man to come and talk to us about a feature of the countryside that most of us see almost every day without really thinking too much about.

His style of presentation perhaps wasn’t everybody’s cup of tea. Rather than waiting for his audience to ask pertinent questions at the end of the 80 minutes, he squandered some of that time by asking us questions from his slides to which he knew few, if any, of us would know the answers, so there were many pregnant pauses.

Even so, we learnt a lot during the presentation. Personally, I thought that a dry stone wall was a dry stone wall. But you could take Trevor blindfold to any part of the country and, by looking at the walls, he could tell you in an instant whether he was in Caithness, Cumbria or the Cotswolds, or his native Derbyshire.

Trevor took us on a pictorial tour of the White and Dark Peaks and Staffordshire Moorlands, pointing out the different size and shape of fields enclosed by dry stone walling, and explaining how these came about, from the perfectly straight ‘strip’ system of farming to large, gradually curving fields which gave a team of eight oxen enough space to turn round.

One of the few correct answers from the floor was that sphagnum moss, found in abundance on dry stone walls, was once used in the production of babies’ nappies, because of its absorbent quality. There is more wildlife in a dry stone wall than in a hedgerow, apparently. And walls harbour more than 2,000 varieties of lichen, often a source of food for the said wildlife and also used in the production of dyes.

And I now know, though he didn’t question us on this directly, that a smoot hole is a gap of appropriate size built into a dry stone wall to allow the free passage of certain creatures (such as rabbits) but not others (such as sheep). It certainly isn’t in my OED, and I’ve now found out that it possibly derives from the Old Norse word smátta, meaning a narrow lane.

You get shooting smoot holes, usually on a grouse moor, and others for rabbits, ducks and geese, badgers or, simply, water. South facing walls surrounding a courtyard would sometimes contain bee holes, and others might incorporate hen nesting boxes. A drawer stone is one which might look indistinguishable to all the others but, if you knew where you were looking, could be pulled out by the fingers and had a hollowed out top to contain money or the keys to a gate.

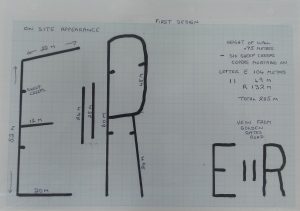

One of Trevor’s most prestigious jobs was to design the controversial EIIR royal cypher which was erected on the hillside near Edensor, on the Chatsworth estate, to celebrate the Queen’s golden jubilee. This consisted of 288.5 metres of dry stone walling, but built only to half normal height so that the shadows cast by the walls on sunny days did not detract from the overall ‘look’ when viewed from the best vantage point a mile or more away.

There was more to designing it than met the eye (literally), because the land where the cypher was erected fell away in three directions and Trevor practised with straw bales before coming up with the final plan which made the characters look askew when viewed from close up but perfectly regular from afar.

I personally, and I suspect many other people felt the same, admired the EIIR royal cypher, but the Peak Park authority decreed that it had only temporary planning permission and the walls eventually had to come down.

But thanks to the skill of Trevor and his fellow dry stone wallers, most examples of their work will still be around for our grandchildren’s grandchildren to admire. They have been part of our heritage for centuries, and will continue to be so.