We all knew how it would finish, of course, but Peter Stubbs kept us enthralled to the very end of the second part of his talk on the War at Sea, 1914 to 1918.

Peter briefly recapped on his previous week’s talk, when we left the British Navy and the British public in good spirits following the annihilation of Von Spee’s squadron in the South Atlantic in December 1914. “Britannia ruled the waves again, but not for long,” he told us.

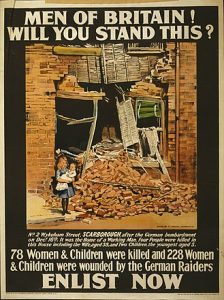

“Only eight days later, at 9am on December 16 and without any warning whatever, high explosive shells smashed into houses, shops and other properties in Scarborough, Whitby and Hartlepool.”

Admiral Franz Hipper had managed to leave harbour in Germany and cross the North Sea undetected. The British Admiralty had cracked German naval codes and warned the fleet of the Germany movement, but Admiral David Beatty failed to intercept either of Hipper’s squadrons, in part due to poor visibility in the North Sea and in part to sloppy signalling by his flag officer.

A post-Scarborough recruitment poster.

Only Hartlepool could have been said to be a legitimate target with its dockyard and factories. In all 86 people were killed and 443 injured. Worst hit were the Bennett family in Wykeham Street, Scarborough. Of seven family members, four were killed.

The British public was outraged. How could the largest and most powerful navy in the world have failed to protect them? But it was also a propaganda coup for Britain. Recruiting in the army and navy shot up, helped by dramatic poster advertising.

There was a partial response nine days later, on Christmas Day, when Britain inflicted the first ever war damage in naval history by air power. Merchant ships had been adapted with hangars on deck for seaplanes, with hoists to lift the planes in and out of the water. When the ships got close enough to the German coast seven seaplanes were launched and carried out a daring bombing raid on the Zeppelin hangars at Cuxhaven.

Further – and more significant – payback came a month later at the Battle of Dogger Bank, when Beatty’s battle cruisers confronted Admiral Hipper, who had led the bombardment of Scarborough. Hipper came out of his home waters with three battle cruisers, three lights cruisers and two flotillas of destroyers.

“The British knew they were coming,” Peter explained. “They had obtained the German naval codes thanks to the brilliance of code breaking staff in Room 40 at the Admiralty. Admiral Beatty was alerted, and set off south from Rosyth to intercept Hipper.” The British ships, all built between 1909 and 1913, were faster than the German opposition, and outgunned them.

“As soon as Hipper’s ship was in range, Beatty signalled to his ships ‘Open fire and engage the enemy.’ It was the first clash between modern battle cruisers in the northern hemisphere.”

Meanwhile, with Britain now at war with Turkey, the Admiralty revisited earlier contingency plans for a joint naval and military attack on the Dardanelles. It was a hazardous plan. The narrows were less than a mile wide and lined with forts and gun emplacements, making it impossible for the navy to ‘stand off’ at a distance and attack out of range of the land based guns. There were also mines laid across the straits.

Five allied ships were lost and three badly damaged, and in all 700 British and French sailors were lost, with nothing achieved.

Back in the North Sea, both sides continued to play cat and mouse, with mixed results. After one particularly bruising encounter, when his flagship Lion was hit twice in five minutes, Beatty reportedly said to his officers: “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today. As Peter explained: “He was quite wrong. What he should have said was ‘there seems to be something wrong with our bloody officers today!’”

However, Britain still had command of the seas. A blockade remained in full force preventing much needed supplies from reaching Germany. The Battle of Jutland in July 1916 was effectively the end of the surface war.

But the peril of Germany’s submarine fleet was ever present. Relations between Germany and the United States had hit rock bottom with the sinking of the Lusitania in May 2015. The Lusitania and her two sister ships were the largest passenger liners in the world. Although she normally travelled at 25 knots, too fast to be at risk from torpedo attack, as she approached the Irish coast she ran into a bank of fog and was forced to reduce speed.

One torpedo was sufficient. It was followed by a large explosion on the ship, probably some of the explosives and armaments she was allegedly carrying, and within 18 minutes she had sunk with the loss of 1,200 passengers, among them 126 US citizens.

The sinking did not bring the US into the war, but it had a significant effect on the attitude of the US government and public opinion. In Germany, meanwhile, the sinking was celebrated and schoolchildren were given a day’s holiday.

The unrestricted German submarine offensive which eventually brought America into the war was ultimately defeated by the convoy system, and this reversal along with a lack of land progress on the western front was bringing Germany to its knees. But although the submarine war had been won, the damage from the U-boat offensive was immense; during 51 months of war, German submarines had sunk 5,282 British, allied and neutral merchant ships.

On 21st November 1918 more than 70 ships of the German High Seas Fleet suffered the ultimate humiliation of surrendering to 370 escorting ships of the allied navies and being escorted to Scapa Flow to be interned there. More than 120 submarines were also taken into internment at Harwich. In an ironic twist, seven months later the captured German fleet at Scapa was scuttled by its own crews to avoid the ships being taken into use by the British navy.

Peter concluded by telling us: “As we all know, the peace was a relatively short one lasting only 20 years. Although apparently forgotten – or at least little mentioned – by our modern day politicians, the two world wars were the real and most important reason for the setting up of the European Community and for countries wanting to be members of it. It seems that our politicians now think that another European war is impossible.”